Pagination Strategies

Pagination is about slicing significant result sets into pages. But how you paginate using offset, keyset, bookmark, cursor, snapshot, hybrid, or exclusion makes a huge difference for performance, consistency, and usability. In this article, I walk through all the common pagination styles, with clear explanations, example queries, trade-offs, edge cases, and guidance for both junior and senior devs.

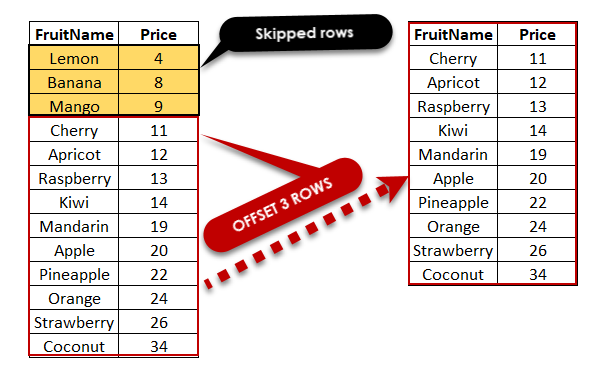

Offset / LIMIT + OFFSET

Offset pagination (using LIMIT ... OFFSET) means “skip N rows, then take M rows.”

How it looks & works

-- page 1:

SELECT * FROM Orders

ORDER BY CreatedAt DESC, Id DESC

LIMIT 50 OFFSET 0;

-- page 2:

SELECT * FROM Orders

ORDER BY CreatedAt DESC, Id DESC

LIMIT 50 OFFSET 50;

-- page N:

OFFSET = (N-1) * 50Suitable for: small tables, admin UIs, occasional paging, or where users rarely go past page 10.

What goes wrong:

- The database typically still has to scan or skip over the first 1,000 rows (or at least process them) — cost grows with offset.

- When data changes (inserts/deletes) earlier in the result, your pages may shift, causing duplicates or omissions.

- Deep paging (huge offsets) becomes slow, sometimes unusable.

- So, although OFFSET pagination is simple and suitable for small data or shallow pages, it doesn’t scale well for large datasets.

In practice, deep offsets (like page 100,000) may take 10x, 50x, or more time compared to early pages, depending on data size and indexing. Some DBs optimize this better with covering indexes (e.g., if all selected columns are indexed), but it still doesn't eliminate the skip cost for large offsets.

You can use EXPLAIN / query plan inspection to determine how many rows are scanned/skipped in OFFSET queries.

Use offset pagination only when datasets are small, or when users expect “jump to page N” and performance is acceptable.

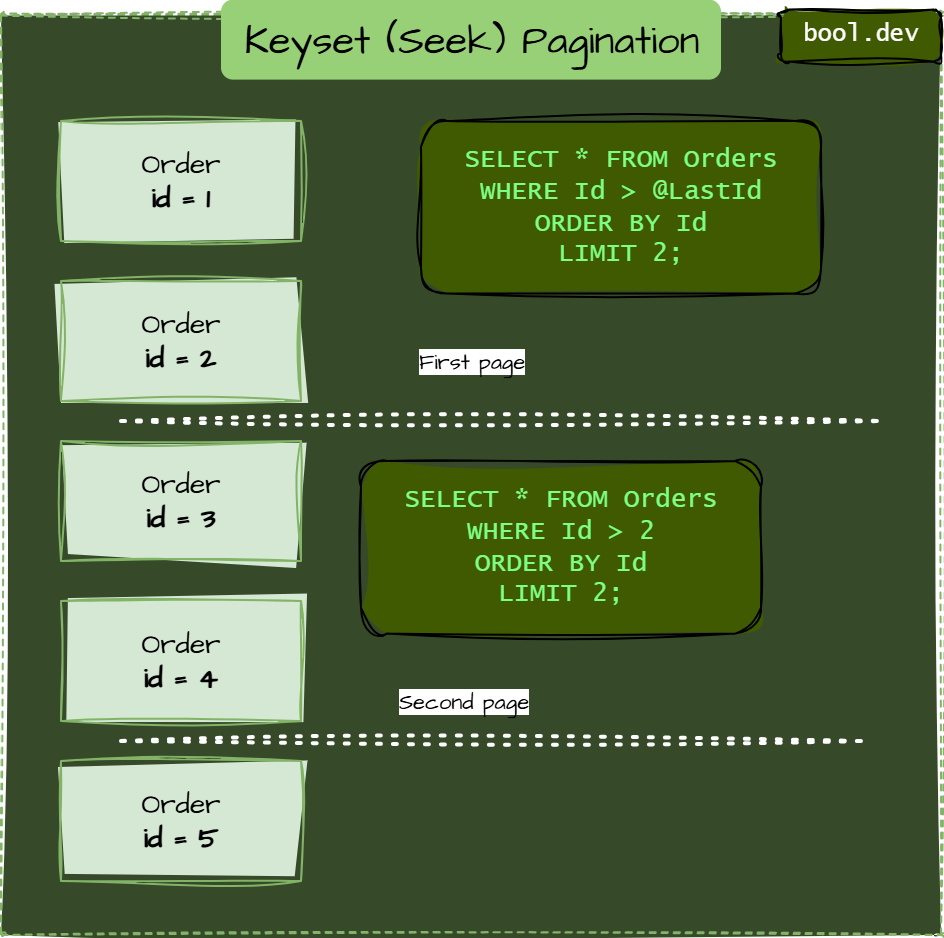

Keyset / Seek pagination

Keyset or Seek pagination means you “seek” from the last seen key value instead of skipping rows.

You don’t say “OFFSET 1000,” you say “give me rows after the last key I saw.”

Imagine we sort by Id (or some monotonic column):

-- first page:

SELECT * FROM Orders

ORDER BY Id

LIMIT 2;

-- assume lastId = 2 from that result

-- next page:

SELECT * FROM Orders

WHERE Id > 2

ORDER BY Id

LIMIT 2;Here, the DB can use the index to jump directly, no skipping needed.

Why this approach is good

- Performance is stable and doesn’t degrade with deep pages.

- Much less scanning work than offset.

- More robust against row shifts (insert/delete) than naive offset.

Trade-offs & edge cases

- You can’t “jump to page 7” easily — you must page sequentially.

- Backward paging requires reversal logic.

- If the cursor record is deleted, continuity may break.

- If sort key is not unique, you need a tie-breaker (e.g.

Id).

Many implementations fetch limit + 1 rows to detect whether there is a next page (i.e. whether hasNext = true).

When implementing, always test with inserts/deletes during pagination to detect skipped/duplicated rows in real scenarios.

Bookmark / Multi-Key Pagination

Bookmark / Multi-Key pagination handles sorting by multiple columns by “bookmarking” a tuple of values and comparing lexicographically.

When your ORDER BY involves multiple fields (e.g. (CreatedAt DESC, Id DESC) or (Score DESC, Date DESC, Id)), a single key isn’t enough — you need to pass a tuple (like (lastDate, lastId) or (lastScore, lastDate, lastId)) to continue correctly.

Example (two columns)

Say you order:

ORDER BY CreatedAt DESC, Id DESCThen your WHERE condition for the next page might look like:

WHERE

(CreatedAt < @lastDate)

OR (CreatedAt = @lastDate AND Id < @lastId)

ORDER BY CreatedAt DESC, Id DESC

LIMIT 50;If you had three fields (e.g. Score DESC, CreatedAt DESC, Id DESC), you’d extend the logic:

WHERE

(Score < @lastScore)

OR (Score = @lastScore AND CreatedAt < @lastCreatedAt)

OR (

Score = @lastScore

AND CreatedAt = @lastCreatedAt

AND Id < @lastId

)

ORDER BY Score DESC, CreatedAt DESC, Id DESC

LIMIT 50;Why use Bookmark pagination

- Allows correct ordering when multiple fields matter.

- You can paginate consistently even when the sort key alone is insufficient.

Complexity & trade-offs

- WHERE logic becomes more verbose and error-prone.

- Higher chance of off-by-one / tie-break bugs.

- Still no “jump to arbitrary page.”

- Backward paging and deletion-edge logic are more complex.

Some ORMs (e.g., SQLAlchemy, Entity Framework) can generate this logic automatically. If columns allow NULLs, add IS NULL checks to avoid bugs. Use a composite index on the ORDER BY columns for performance. For backward paging, invert inequalities and ORDER BY direction (e.g., ASC instead of DESC).[

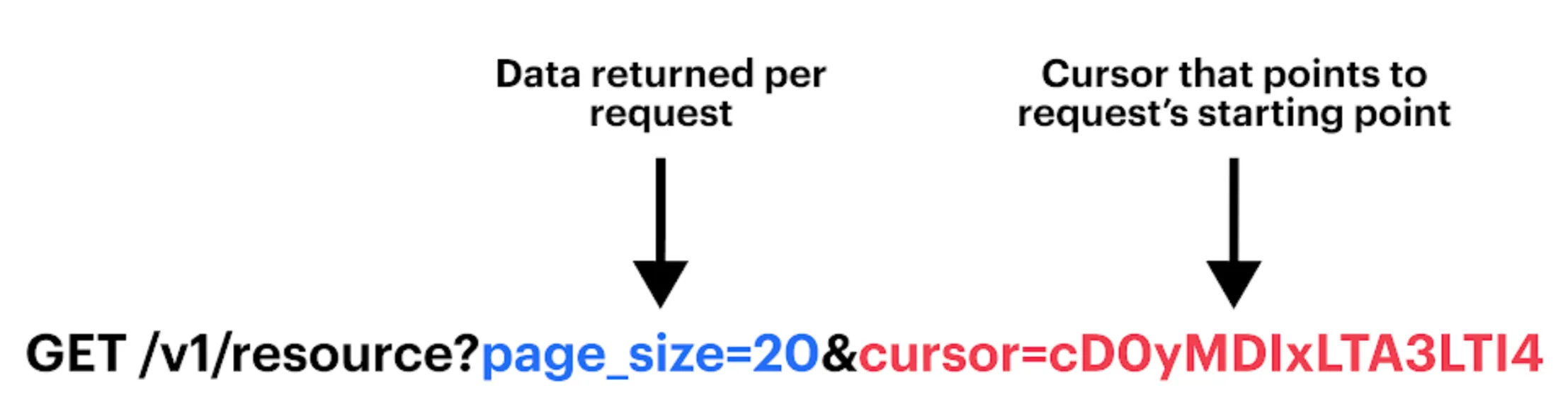

Cursor / Token Pagination

Cursor/Token pagination is a layer on top of keyset/bookmark, where clients receive an opaque token (cursor) instead of raw key values.

Under the hood, it's still keyset/bookmark, but the client receives something like "cursor":"eyJ0aW1lIjoiMjAyNS0xMC0xMSIsImlkIjoxMjM0fQ==".

How it works

- You fetch a page using keyset or bookmark logic.

- You take the last row’s key(s) (e.g.

(CreatedAt, Id)) and encode them (e.g., Base64, JSON) into acursorvalue. - Return that cursor to the client (alongside the results).

- On the subsequent request, the client provides

cursor=…. - You decode it internally and then use the same keyset/bookmark logic.

WHERE (CreatedAt, Id) > (decodedDate, decodedId)

ORDER BY CreatedAt, Id

LIMIT 50;Pros:

- Clients don't see the internal schema or rely on internal keys.

- You can change internal logic later without breaking clients.

- Cleaner API interfaces.

Cons:

- Adds encoding / decoding logic.

- Harder to debug (cursor is opaque).

- Underlying keyset limits still apply (no random jumps, backward logic complexity).

You should include the cursor version or schema in the token so that future internal changes don’t break old cursors. Handle invalid/stale cursors gracefully (e.g., reset to first page or return an error).*

Many APIs render pagination metadata along with results, e.g. { "items": [...], "pagination": { "next_cursor": "...", "has_next": true, "has_prev": false } }

For security, sign or encrypt the cursor to prevent tampering. Cursors can include extra state (e.g., filters, sort params), but avoid bloat. Rate-limit repeated invalid cursors to prevent abuse

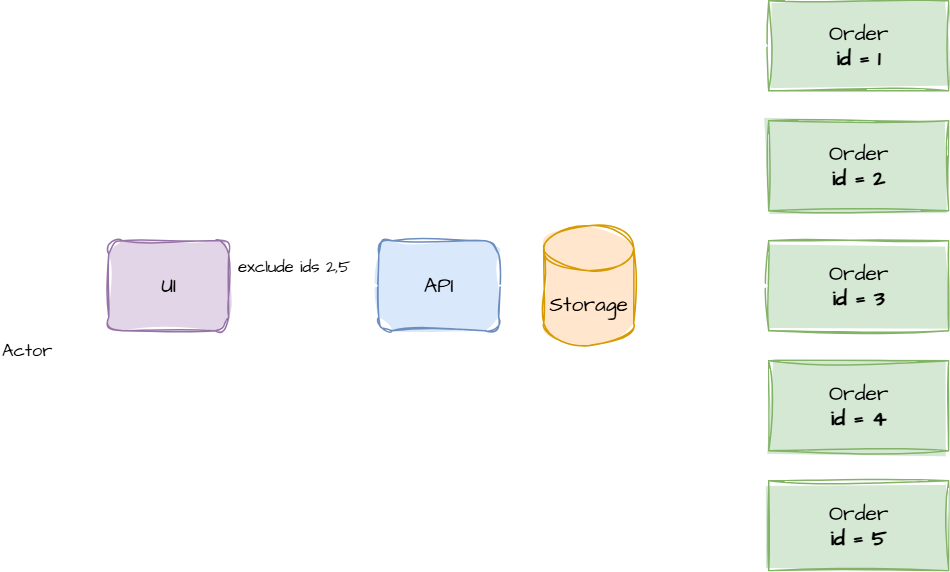

Exclusion / Seen-ID Pagination

Exclusion/Seen-ID pagination means sending a list of items (IDs) that the client has already seen and excluding them from subsequent queries.

Rather than relying purely on order or cursor, you “subtract out” seen items:

SELECT *

FROM Items

WHERE Id NOT IN (@seenIds)

ORDER BY <some sort>

LIMIT 50;When to use:

- Merging multiple streams or sources

- When the ordering is unstable or complex beyond simple ascending/descending

- In recommendation engines or federated APIs

Downsides:

- Large

NOT INlists can degrade performance. - Harder to index/optimize for exclusion.

- Payload/memory overhead (client must carry the list).

- Complexity in deduplication and ordering.

If exclusion lists grow large, consider segmenting them (e.g., batch exclusions) or using a temporary table / join instead of NOT IN. This style rarely offers good backward paging without re-fetching or more logic overhead.

For better performance, use NOT EXISTS (subquery) or LEFT JOIN ... WHERE seen.Id IS NULL, which can leverage indexes. If lists are huge, consider temp tables or Bloom filters in advanced DBs. Additional use cases: social feeds (excluding seen posts) or search with deduping. Server-side storage of seen IDs (e.g., session-based) can reduce client payload.

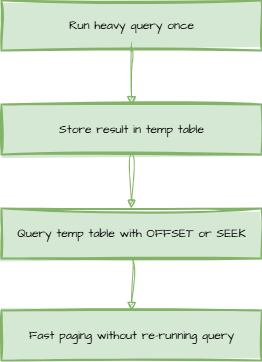

Snapshot / Materialized / Cached Pagination

Snapshot pagination means you freeze a query’s result (materialize it) and then paginate over that static snapshot.

When the underlying data can change, a snapshot gives you a stable view during a user’s paging session.

Pros:

- Pagination becomes fast and stable

- No surprises from concurrent data updates during paging

- Excellent for reports, exports, and dashboards

Cons:

- Snapshot staleness — you should refresh/expire or rebuild

- Extra storage and maintenance costs

- Doesn’t reflect live data changes until snapshot refresh

You may choose TTL-based snapshot expiration or incremental refresh (e.g., delta updates) for better freshness. When the snapshot is large, you can combine it with keyset pagination internally for efficiency.

Tools like PostgreSQL materialized views (with REFRESH) or Redis for caching can implement this. Use incremental updates via triggers or CDC to maintain freshness, rather than complete rebuilds. Offsets work well on snapshots since data is static. If user-specific, partition, or use per-session TTLs to manage storage.

Hybrid / Fallback Strategies

Hybrid/Fallback means combining two or more pagination strategies and switching between them based on conditions (e.g., depth, UI, context).

In many real systems, one strategy isn’t enough. So you might:

- Use offset for the first few pages (where offset cost is low), then switch to keyset/cursor for deeper pages.

- Support both offset-based and cursor-based APIs (clients choose which suits them).

- Chunk/partition the data, then apply cursor logic within chunks.

- Use offset in admin interfaces, cursor in public APIs, etc.

- This gives flexibility, but you must handle switching logic and edge cases.

Real-world examples: LinkedIn uses offsets earlier than cursors. Switch at thresholds like page 10 or offset > 500 based on perf metrics.

Comparison & Trade-off Summary

| Pattern | What It Means | Strengths | Weaknesses / Trade-offs | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offset / LIMIT + OFFSET | Skip N rows, then take M | Simple, jump to arbitrary page | Performance degrades with high offset; shifting data issues | Small tables; shallow paging; admin UIs |

| Keyset / Seek | Use last seen key to fetch next rows | Stable performance, efficient index use | No random jumping; backward logic harder; tie-breaker needed | APIs, infinite scroll, large data |

| Bookmark / Multi-Key | Use a tuple of keys for multi-column ordering | Handles complex sort orders correctly | Complex WHERE logic, more edge cases | Sorting by multiple fields (score + time + id) |

| Cursor / Token | Wrap keyset/bookmark in an opaque client-side token | Clean API, schema decoupling | Same limits as keyset + encoding/decoding complexity | Public APIs, partner APIs |

| Exclusion / Seen-ID | Exclude already seen items via ID list | Useful when ordering is unstable / merging sources | Performance issues with large exclusion sets | Recommendation systems, federated APIs |

| Snapshot / Materialized | Freeze results then paginate static snapshot | Stable, fast paging over fixed view | Snapshot staleness, extra maintenance | Reports, exports, dashboards |

| Hybrid / Fallback | Switch between strategies based on context | Flexible, mix of usability + performance | More complexity and branching logic | Systems with varied usage modes |

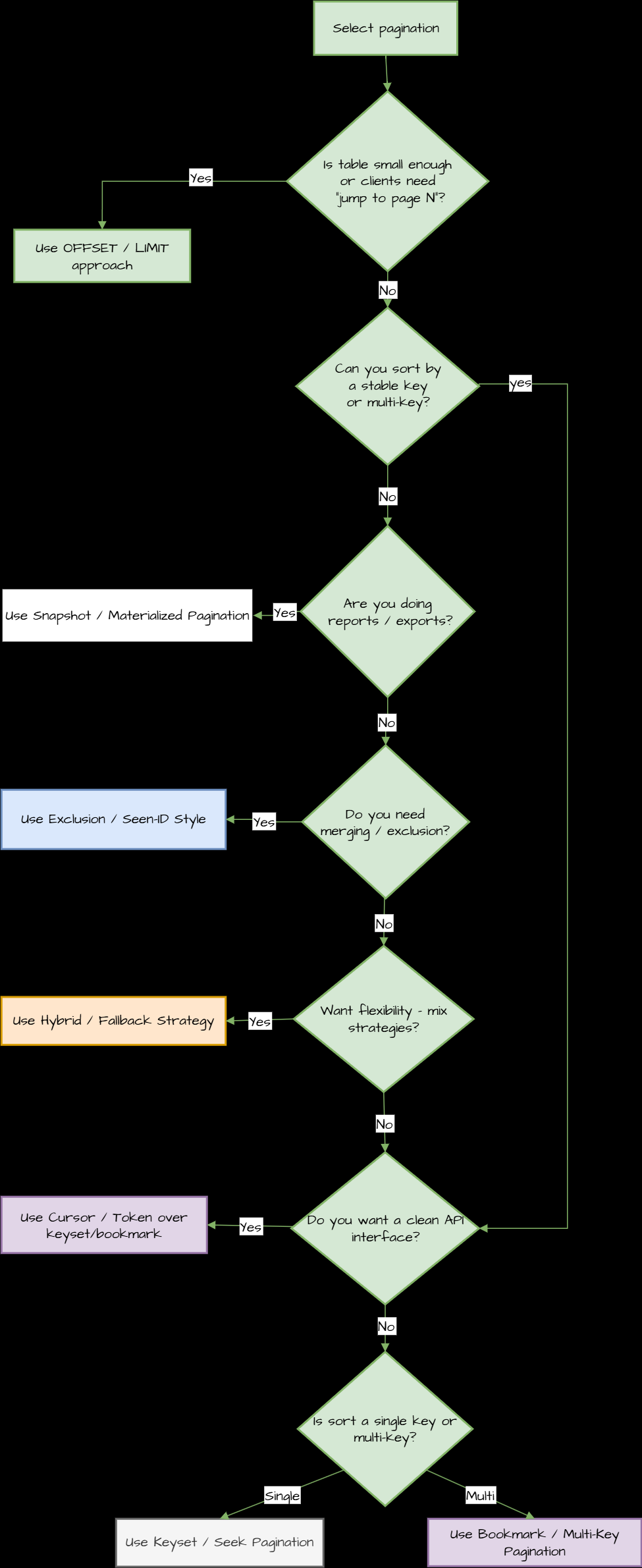

Cheatsheet for making a decision:

NoSQL Pagination Equivalents

While this article focuses on relational DBs, equivalents exist in NoSQL: DynamoDB uses LastEvaluatedKey (keyset-like), MongoDB's skip/limit has offset pitfalls, and Elasticsearch uses search_after (bookmark-style).